[To come: an evaluation of Edward Said’s Orientalism.]

Wendy Doniger thinks that Hinduism has suffered from a reverse Pizza Hut. A “Pizza Hut” is when a simplified form of something wonderful gets popularized, and this inspires people to seek out the real thing. But the popularization of Hinduism seems to have flattened it. Pizza Hut inspired people to look for better pizza: Hinduism got lost in translation. Elvis gave the Blues a big Pizza Hut. Starbucks gave coffee shops a real Pizza Hut treatment. Instead, Doniger claims, Hinduism’s fascinating multitudes have been standardized for export. The simplified image of Hinduism we have has seemingly eclipsed the diversity of India’s religions. Her proposed tonic: increase the conversation around Hinduism and invite everyone in: this book review is my humble attempt to promote that conversation. Today’s woke will balk at a white woman lecturing Hindu Nationalists about their own heritage. Those on the right will reject the liberal toleration of difference her Hinduisms seem to invoke. Ladies and Gentlemen, our moment is filled with contradictions. Consider the difficulties involved in filling the category “Hindu.”

“Only after the British began to define communities by their religion, and foreigners in India tended to put people of different religions into different ideological boxes, did many Indians follow suit, ignoring the diversity of their own thoughts and asking themselves which of the boxes they belonged in. Only after the seventeenth century did a ruler use the title Lord of the Hindus (Hindupati). Indeed, most people in India would still define themselves by allegiances other than their religion. The Hindus have not usually viewed themselves as a group, for they are truly a rainbow people, with different colors (varnas in Sanskrit, the word that also designates ‘class’), drawing upon not only a wide range of texts, from the many unwritten traditions and vernacular religions of unknown origins to Sanskrit texts that begin well before 1000 BCE and are still being composed, but, more important, upon the many ways in which a single text has been read over the centuries, by people of different castes, genders, and individual needs and desires… the books that Euro-Americans privileged (such as the Bhagavad Gita) were not always so highly regarded by ‘all Hindus,’ certainly not before the Euro-Americans began to praise them. Other books have been far more important to certain groups of Hindus but not to others” (p 25).

None of this would impress if Wendy Doniger didn’t happen to be a genius, an expert, an authority, the real deal, and if her work wasn’t exhaustively documented and flawless in its articulation. As for a definition of Hinduism, she frankly admits defeat and offers instead to give us one understanding of Hinduism that weaves together many threads without claiming to be definitive. I’m not an expert on Hinduism or India, but I can tell when someone knows their domain well, and it was a pleasure to watch such a powerful scholar stretch her legs. You should read and reread The Hindus: An Alternative History. It is nearly 700 pages long, and it will save you a lot of time and confusion given the scope of its material: the story of Hinduism from pre-History to Allen Ginsberg with no major trend excluded. This will mean calling in the voices internal to Hinduism that are often excluded and recognizing the give and take between Sanskrit, the language of the Vedas, and the multitude of vernaculars that feed into Sanskrit like so many tributaries to the Ganges.

Wendy Doniger’s monumental work challenges the conventional, often sanitized, portrait of Hinduism that many in the West have come to expect. In “The Hindus: An Alternative History,” she presents Hinduism not as a single, static entity but as a vibrant tapestry of countless voices, traditions, and practices that have evolved over millennia.

The book also serves as a corrective to both Western Orientalist portrayals and contemporary political appropriations. Doniger exposes how historical and scholarly biases have often simplified Hinduism into a monolithic entity, neglecting the internal debates and alternative voices that have enriched its history. By tracing the evolution of religious ideas—from the early Indus Valley civilizations, through the formative Vedic period, to the complex mythologies of later epochs—she invites readers to see Hinduism as an ever-changing, “bricoleur” tradition that continuously reconstructs itself.

Ultimately, Doniger’s alternative history is both a scholarly tour de force and a passionate call for a broader, more inclusive conversation about Hinduism—one that respects its inherent contradictions, its deep historical roots, and its ongoing transformation in the modern world.

The modern Western encounter with Hinduism included Aryan myths that Doniger is quick to dispel. The earliest traces we have of civilization in India are in the Indus valley, but because India is a land that cannot raise horses, and the Vedas are a story where horses play a key role, it is unlikely that the Vedas came from the Indus valley culture. They came from outside India, and that is all we know for sure about them. Naturally, this set off a gold rush of speculation. The Aryan myth would be that horse riding people from outside India brought the Vedas, a myth that Hitler borrowed to stoke Aryan pride. The problem of course is that this is all fantasy. The reality, what we can see of it, is rich and complex. The original Vedic texts seem to reveal to us an original syncretism, a blending of systems.

“Hinduism, like all cultures, is a bricoleur, a rag-and-bones man, building new things out of the scraps of other things… A good metaphor for the mutual interconnections between Vedic and non-Vedic aspects of Hinduism is provided by the myth with which this chapter began…’When the three worlds were in darkness, Vishnu slept in the middle of the cosmic ocean. A lotus grew out of his navel. Brahma came to him and said, “Tell me, who are you?” Vishnu replied, “I am Vishnu, creator of the universe. All the worlds, and you yourself are inside me. And who are you?” Brahma replied, “I am the creator, self-created, and everything is inside me.” (from the Kurma Purana)’… ‘Vishnu and Brahma Create Each Other.’ Each says to the other, ‘You were born from me,’ and both of them are right. Each god sees all the worlds and their inhabitants (including himself and the other god) inside the belly of the other god. Each claims to be the creator of the universe, yet each contains the other creator… Vedic and non-Vedic cultures create and become one another like this too throughout the history of Hinduism. This accounts for a number of the tensions that haunt Hinduism throughout its history, as well as for its extraordinary diversity.” (Doniger p.101-102).

https://hindumythologybynarin.blogspot.com/2015/01/origin-of-lord-vishnu-and-lord-brahma.html

Below is a chapter‐by‐chapter summary of Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternative History, which re‐examines Hinduism as a diverse, multifaceted tradition rather than a single, monolithic religion.

CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION: WORKING WITH AVAILABLE LIGHT

Doniger opens by laying out her methodological framework. She explains that reconstructing the history of Hinduism involves working with “available light” – that is, a mosaic of texts, oral traditions, and archaeological evidence.

In the opening chapter, she explains that Sanskrit was not the primordial or naturally spoken language of the people but rather a refined, “secondary revision” that emerged from a minority. She argues that the natural, vernacular tongues (like Prakrit) came first, and Sanskrit was later fashioned into an “artificial” language—a language whose power lay precisely in its nonintelligibility and inaccessibility, which set an elite group apart. In this way, Sanskrit became not only the language of sacred texts but also a marker of social and cultural power, even as it absorbed influences from the oral and popular traditions it eventually encountered.

CHAPTER 2 – TIME AND SPACE IN INDIA 50 Million to 50,000 BCE

In Chapter 2 Doniger questions the certainties that early archaeologists and scholars brought to the study of India’s deep past. Rather than accepting a view of the Indus Valley as a static, timeless civilization—one neatly encapsulated by fixed geological markers or catastrophic flood events—she suggests that such assumptions reflect a modern, linear mindset that misreads the fluid nature of Indian prehistory. Doniger outlines the geological formation of the subcontinent – from ancient plate tectonics and the drifting of landmasses (even suggesting that India was “outsourced” from Africa) to the early human migrations arriving by sea. In doing so, she shows how the natural environment and epic flood myths (which later become central to Hindu cosmology) set the stage for the cultural developments to come. Doniger points out that the dramatic flood myths and the associated imagery (like submerged cities and recurring cycles of creation and destruction) have often been taken by archaeologists as literal evidence of a single, catastrophic event or an unchanging cultural foundation. Instead, she argues that these narratives are best understood as part of a cyclical cosmology: they are as much about the constant transformation and reconstitution of the world as they are about any historical “fact.” In her view, the archaeological record should not be forced into rigid, Western categories of “beginning” and “end” but appreciated for its inherent dynamism, where myth and material reality continuously inform one another.

CHAPTER 3 – CIVILIZATION IN THE INDUS VALLEY 50,000 to 1500 BCE

Here the focus shifts to the urban Indus Valley Civilization (IVC). Doniger reviews its material culture – uniform brick construction, elaborate seals, and a highly organized urban plan – and raises the tantalizing possibility that many of its symbols and ritual practices may have seeded later Hindu traditions. Although the IVC left no deciphered texts, its art and artifacts speak to a sophisticated religious sensibility that influenced subsequent cultural developments.

Here Doniger uses the arrival of horses as a symbol of profound cultural transformation. She notes that horses—unsuited to local breeding conditions and thus necessarily imported—arrived in Northwest India around 1700–1500 BCE, marking the point when nomadic, Indo‐Aryan groups began composing the Rig Veda. Their introduction signaled a break from the settled, urbanized traditions of the Indus Valley civilization. Rather than being a mere practical development, horses came to represent the new elite’s power and mobility, as well as the onset of warfare and chariotry that would reshape society. In Doniger’s account, horses are emblematic of both the technological innovation and the symbolic assertion of a foreign, transformative influence on India’s ancient cultural landscape.

Doniger develops the dichotomy Indus, having material culture with no written documents, to the Vedic, having written documents but no surviving material culture, into a metaphor for how we understand these early civilizations. This stark contrast serves as a metaphor for the limits—and the possibilities—of how we come to know the past. On one side, the Indus Valley civilization has left us a rich array of physical objects—artifacts, seals, and urban layouts—but no deciphered written records; these “things without words” offer us a glimpse into daily life, technology, and material practices yet remain silent on beliefs and social organization. On the other side, the Vedic tradition gives us a vast corpus of texts—“words without things”—that convey ideas, rituals, and mythic narratives but leave little behind in the way of tangible material culture that might tell us about everyday living. Like one of Hinduisms exiled kings, Arjuna or the Panduvas, the spiritual texts seem to have left their home behind over the course of these centuries to live off the land in India’s forests. By juxtaposing these two kinds of evidence, Doniger is urging us to recognize that our understanding of early civilizations is inherently partial. We are forced to piece together history from disparate fragments: the material and the verbal, each incomplete on its own, yet together suggesting a dynamic, evolving culture rather than a static, neatly bounded entity. This metaphor not only highlights the challenges inherent in reconstructing prehistory but also critiques the bias of privileging written records over material remains in our historical narratives.

CHAPTER 4 – BETWEEN THE RUINS AND THE TEXT 2000 to 1500 BCE

As the IVC declines, a new cultural and religious order begins to emerge. Between 2000 and 1500 BCE, as the urban brilliance of the Indus Valley began to wane, India underwent a profound transformation not only in its material culture but also in its social fabric. Alongside the decline of the sophisticated urban centers, the agricultural revolution took hold. This revolution reshaped everyday life—cultivation methods demanded new forms of labor organization that in turn reconfigured gender relations. As agriculture became more central, women’s roles evolved from being primarily embedded in communal and ritualistic practices to engaging in more formalized, productive activities within the household and community. Over time, these shifts contributed to the emergence of monogamous marriage as a stabilizing institution, gradually replacing earlier, more fluid marital practices.

Doniger harnesses this period of dynamic change to highlight the powerful metaphor of the exiled prince. Here, the prince’s wandering mirrors not just the disintegration of an old urban order but also the deep social realignments driven by agriculture—the restructuring of gender roles and the establishment of a monogamous family as a new form of social order. In this narrative, the “Odysseus” or exiled prince, cut off from a lost legacy and in search of renewal, becomes a symbol of the human quest for the divine. His journey reflects the broader cultural yearning to rediscover and restore a primordial order that has been disrupted by both material decline and transformative social practices.

In this way, the material situation of the era—with its collapse of an artifact-rich civilization juxtaposed against emerging, text-based traditions and new social institutions—serves as a forerunner to later epic narratives such as the Ramayana. Just as the prince’s exile prefigures the epic’s themes of duty, loss, and eventual restoration, the agricultural revolution’s impact on gender and marriage underscores a deeper, ongoing search for order and transcendence in the face of change .

CHAPTER 5 – HUMANS, ANIMALS, AND GODS IN THE RIG VEDA 1500 to 1000 BCE

Doniger turns her attention to the Rig Veda, the oldest corpus of Sanskrit literature. This chapter explores the interplay between humans, animals, and divine forces as described in the hymns. The ritual sacrifices, the role of nature, and the early cosmological ideas laid down here become the building blocks of Hindu mythology and set the stage for the intricate metaphors that follow in later periods.

In Chapter 5 Doniger describes the transition from different systems for improving karma, emphasizing three major phases.

In the earliest Vedic traditions, animal sacrifice (yajna) was central to religious practice. It was believed that offering animals in sacrifice pleased the gods and helped maintain cosmic order (rita). The sacrificial victim, often a horse or a bull, was symbolically imbued with power and then offered to the deities to secure good karma for the sacrifice.

As religious thought evolved, concerns about violence against animals led to the substitution of plant-based offerings. This shift was influenced by the Upanishads and Brahmanas, which introduced the idea that oblations of rice and barley could symbolically replace animal offerings. Some Vedic texts even depicted the gods as no longer consuming physical food but merely being satisfied by the sight of sacrificial offerings.

The final transition occurred as karma came to be understood not just as ritual action but as personal behavior. Renouncers (sannyasis) and new religious movements like Buddhism and Jainism rejected sacrificial rituals altogether, promoting the idea that one's ethical actions determined their future rebirth. Jainism emphasized ahimsa (non-violence), which led to the rise of strict vegetarianism. Hinduism gradually incorporated these ideas, linking non-violence to spiritual purity and good karma.

This transition from animal sacrifice to vegetarianism was not just an ethical shift but also a response to political and religious competition. Buddhism and Jainism, which rejected sacrificial rituals, attracted powerful patrons, leading many Hindus to redefine their practices in ways that emphasized non-violence and ethical conduct over ritual sacrifice.

CHAPTER 6 – SACRIFICE IN THE BRAHMANAS 800 to 500 BCE

In the Brahmanas, ritual sacrifice reaches a high level of complexity. Doniger details how these texts elaborate on the intricacies of sacrifice—not merely as a ritual act but as a mode of communication between humans and the divine. This chapter examines how these practices both reflected and reinforced the emerging social orders, even as they introduced ambivalences about violence and purity.

In the Rig Vedic era, hymns often expressed uncertainty about divine powers, pleading with gods for help. However, as society developed and settled in the Ganges region, the Brahmanas (commentaries on the Vedas) introduced a more structured and confident theological approach. The belief that specific mantras could control divine forces replaced earlier doubts.

One striking example of this change is the Brahmanas’ reinterpretation of an ambiguous Vedic creation hymn that originally asked, “Who is the god whom we should honor with the oblation?” To provide a definitive answer, the Brahmanas declared that the god’s name was literally Who (Ka in Sanskrit), transforming an open-ended question into an assertion of divine certainty.

Doniger attributes this shift to changes in social organization. As Vedic people moved from the Punjab to the fertile lands of the Ganges, they adopted more settled lifestyles. This shift led to a more hierarchical society where religious authority became concentrated among Brahmins, who claimed exclusive knowledge of sacrificial rituals. Unlike the Rig Vedic period, where multiple interpretations of the divine coexisted, the Brahmanas sought to standardize and control religious knowledge.

A key metaphor in this chapter is the myth in which Vishnu and Brahma create each other. This reflects how Vedic and non-Vedic traditions influenced each other, shaping Hinduism’s evolving theological landscape. Just as the gods define each other’s existence, society and religious beliefs co-create one another, leading to ongoing tensions between rigid orthodoxy and theological openness.

Like a stew with more and more ingredients, society became more complex: like a crust of bread in an oven religious ideas became more rigid. The earlier gods of the Rig Veda, who had been depicted as powerful but approachable, gradually took on characteristics resembling earthly rulers—jealous, hierarchical, and eager to control human actions. The increased importance of sacrifices and rituals in the Brahmanas reinforced the social power of Brahmins, further distancing the divine from the everyday lives of ordinary people.

In summary, Chapter 6 illustrates how Hindu society transitioned from an era of open-ended religious inquiry to one of increasing doctrinal rigidity, where Brahmins asserted greater control over both religious practice and people's relationship with the divine. This transformation was deeply tied to societal developments, reflecting the mutual evolution of social hierarchy and religious thought.

CHAPTER 7 – RENUNCIATION IN THE UPANISHADS 600 to 200 BCE

Marking a profound shift, the Upanishads redirect focus inward. Here, Doniger lays out the move away from external ritual sacrifice toward introspection, meditation, and renunciation. She shows how the philosophical inquiries into the self and ultimate reality began to transform Hindu religious practice into a quest for inner truth, setting in motion ideas that would later inform both ascetic traditions and mystical practices.

In early Vedic traditions, religious practice centered around external sacrifices, particularly the fire sacrifice (yajna), which was seen as essential to maintaining cosmic order. However, by the time of the Upanishads (c. 600–200 BCE), some sages began to challenge this framework, suggesting that true spiritual progress came not from offering animals or substances into the fire but from self-discipline, meditation, and inner sacrifice.

This transformation parallels Rene Girard’s notion that societies initially rely on physical sacrifice to manage violence and social cohesion, but over time, they seek alternative, less tangible forms of expiation. In Girard’s anthropology earlier myths speak of trickster gods, Loki or Coyote, who transgress and are punished, but under that cover story he hears the result of mimetic competition over limited resources, leading to conflict and the deaths of innocents. For Girard the final stage is Jesus, the sacrificed (lynched?) god of universal forgiveness: the innovation being that this time the story is told from the point of view of the sacrificial victim. Like Christian mystics internalized Jesus’ ethos of self sacrifice, the Upanishadic sages internalized the idea of sacrifice, directing it toward the self—an internalized discipline of renunciation (samnyasa), detachment from material possessions, and meditation.

The Upanishads introduce figures like the renunciant (sannyasi), who withdraws from society to pursue spiritual liberation (moksha). These ascetics believed that rather than engaging in sacrifices, one should renounce worldly life entirely, leading to an emphasis on contemplation and the realization of the self’s unity with brahman (the ultimate reality). This marks a significant departure from the earlier Brahmin-dominated ritualistic tradition.

https://www.indica.today/research/research-papers/the-vedas-and-the-principal-upanishads-part-ii-a/

Interestingly, this movement did not remain confined to Brahmins. Doniger points out that kings (kshatriyas), such as Jaivali Pravahana and Janaka of Videha, also played a role in advancing renunciatory ideas, suggesting a broader shift in spiritual authority. In some Upanishadic stories, Brahmins are portrayed as students learning from kings—a striking reversal of earlier Vedic norms.

The Upanishads present two main spiritual paths:

The Path of Smoke (Samsara): This represents continued participation in the world, including family life, procreation, and ritual sacrifice. Those on this path are reborn into the cycle of life and death.

The Path of Fire (Moksha): This involves renouncing worldly attachments and seeking liberation through knowledge and inner discipline. Those who achieve moksha escape the cycle of rebirth and merge with brahman.

Girard’s theory of sacrifice suggests that societies must continually refine how they manage violence and human desires. The Upanishadic renunciatory movement can be seen as an attempt to redirect religious energy away from external, often violent practices and toward a more introspective and personal discipline.

CHAPTER 8 – THE THREE (OR IS IT FOUR?) AIMS OF LIFE IN THE HINDU IMAGINARY

This chapter explains the classical Indian framework of Purusharthas—the aims of life. Doniger discusses dharma (duty/ethics), artha (prosperity), and kama (pleasure), with some traditions adding moksha (liberation). She highlights how these guiding principles coexist in a delicate balance, representing both the aspirations and inherent contradictions within the Hindu worldview.

The Hindu “aims of life” form an intricate, interlocking system that both guides and reflects the lived experience of happiness and fulfillment. Originally, Hindu thought focused on a trio—dharma, artha, and kama—but over time a fourth aim, moksha, was added. Each aim addresses a different sphere of human life and the strategies for pursuing them are often organized both by the roles one occupies (linked to class or varna) and by the stage of life (the ashrama system).

Dharma, the most multifaceted of the aims, encompasses duty, ethics, religion, and the maintenance of social and cosmic order. It is not a one-size-fits-all mandate; rather, it becomes a personalized duty (sva‑dharma) that is shaped by one’s class and gender and is expected to evolve over one’s lifetime. For example, the dharma of a Brahmin involves learning and teaching sacred texts, while that of a Kshatriya is oriented toward leadership and even warfare. This dynamic quality of dharma is central to its role in maintaining balance within the cosmos and society, even as it sometimes leads to internal tensions—such as the conflict between upholding nonviolence and engaging in sacrificial violence.

Artha represents the pursuit of wealth, political power, and material success. It is seen as essential for sustaining life and for enabling the fulfillment of one’s social responsibilities. While artha is a practical, worldly aim, it is meant to be pursued in a way that does not compromise dharma. In this sense, wealth is not merely an end in itself but a means to secure the well-being of oneself and one’s community.

Kama covers the broad spectrum of desire and pleasure, not limited to sexual ecstasy but extending to all forms of sensual enjoyment—music, art, fine food, and even the aesthetic pleasures of life. It affirms that the pursuit of beauty and enjoyment is an integral, natural aspect of human existence, so long as it is balanced with the other aims.

Moksha, the ultimate aim, stands apart as the quest for liberation from the cycle of rebirth. It is typically associated with the renunciant life and represents a transcendent goal beyond the worldly pursuits of pleasure, wealth, and duty. The texts describe moksha as a kind of release that is in constant dialogue with dharma: the renouncer’s path emerges as a response to the limitations and eventual impermanence of worldly existence.

The organization of these aims is itself a subject of debate in the tradition. Early texts and the ashrama system offered multiple options for how one might pursue these goals at any point in life. In the earliest formulations, the four ashramas—the chaste student, the householder, the forest dweller, and the renouncer—were not seen as fixed life stages but as alternative lifestyles open to an individual at any time. Later, however, the system became more sequential: childhood is for learning (acquiring artha and the knowledge that underpins dharma), the prime of youth is for the enjoyment of kama, and later life is ideally devoted to upholding dharma and ultimately seeking moksha. Various strategies were proposed to reconcile the tensions between these aims. For instance, some texts advocate for a symbiotic relationship in which householders support renunciants (and in turn receive spiritual blessings), while others suggest compromises such as temporary renunciation or the idea that properly performed household duties can themselves be a form of renunciation.

In sum, Chapter 8 portrays the purusharthas (the aims of life) as a dynamic and interdependent set of goals. They are organized in ways that reflect both the social hierarchy (with different roles and responsibilities prescribed to different classes) and the natural progression of life. Rather than being mutually exclusive, these competing goods are meant to be balanced; a full and happy life is seen as one in which a person skillfully integrates duty, material success, sensual pleasure, and the aspiration for ultimate liberation. This elegant balancing act, with its inherent tensions and resolutions, is at the heart of the Hindu imaginary of what it means to live well and meaningfully.

https://www.drikpanchang.com/vedic-mantra/gods/lord-rama/rama-mantras.html

CHAPTER 9 – WOMEN AND OGRESSES IN THE RAMAYANA 400 BCE to 200 CE

The Ramayana displays a complex understanding of gender. The narrative is read as a site where ideals and anxieties about women are projected, from revered heroines to monstrous figures. This duality illustrates how myth can both oppress and empower, revealing the contested nature of female identity and social roles in ancient India.

The monkey hero Hanuman, also a divine avatar, serves as a reflection of Rama’s moral struggles. While Rama, the divine avatar, frequently forgets his godly nature and is bound by rigid dharma, Hanuman, the monkey avatar, embodies devotion, adaptability, and emotional depth. Their stories mirror each other—both forget their true powers at times, both face tests of their identity, and both undertake great journeys—but Hanuman’s uninhibited expression of emotions and unwavering loyalty contrast sharply with Rama’s severe and often morally ambiguous decisions.

The story of Valin, the monkey king, serves as a crucial reflection of Rama’s own struggles with justice and betrayal. Valin and his brother Sugriva, much like Rama and Bharata, are brothers caught in a succession conflict. Valin, like Rama, is the rightful king but is exiled due to misunderstanding and treachery. Sugriva, in a situation parallel to Bharata, takes over the throne but needs outside help—Rama in Sugriva’s case, and Bharata’s army in Rama’s. However, Rama’s intervention in the monkey kingdom is morally questionable—he kills Valin by shooting him from behind, an act considered cowardly and unfair in the warrior code. This mirrors the way in which Rama is later accused of unjustly banishing Sita despite her innocence. Both Rama and Valin are kings whose adherence to dharma is complex and problematic, but while Valin is punished with death for his perceived failings, Rama, despite his own moral failings, is ultimately upheld as a just ruler. Doniger uses this parallel to suggest that Ramayana is not just a tale of divine righteousness but a nuanced exploration of human limitations, with Hanuman standing as a counterpoint to Rama’s often rigid morality.

Wendy Doniger's analysis of women in The Ramayana reveals a complex and often contradictory attitude toward gender and dharma. The epic constructs an idealized vision of womanhood through Sita, who becomes the archetype of the devoted and chaste wife, yet it simultaneously introduces "shadow women" who challenge this ideal. Doniger notes that Sita, while exalted as the ultimate symbol of virtue, is also portrayed as passionate and strong-willed in some versions of the text. However, later Brahminical interpretations suppress these qualities, emphasizing her submissiveness instead. The existence of figures like Kaikeyi, Surpanakha, and the ogress women further complicates the narrative, as they embody traits that Sita is supposed to reject—ambition, sexuality, and defiance.

At the heart of The Ramayana’s gendered discourse is the question of a woman's dharma, which is depicted as unwavering loyalty and obedience to her husband. Sita’s ordeals—her trial by fire and ultimate banishment—illustrate how rigid expectations of female virtue can lead to suffering and injustice. This is reinforced by the harsh treatment of women like Surpanakha, who is physically mutilated for expressing sexual desire, a punishment aligned with traditional dharma texts that condemn "promiscuous" women. However, alternative retellings of The Ramayana challenge this dominant narrative. Folk versions and Dalit interpretations depict Sita as defiant, even rejecting Rama after her exile. Some communities have even reinterpreted her suffering as a critique of patriarchal oppression, using her story to advocate for women’s rights. In this way, Doniger argues that The Ramayana simultaneously upholds and resists oppressive gender norms, revealing the tension between dharma as an ideal and its real-world consequences for women.

Quothe Doniger: “all the fun is in the women and the monkeys” because these elements inject the Ramayana with a deliciously subversive, ambiguous, and lively quality that contrasts sharply with the otherwise idealized, even rigid, portrayals of human perfection. Regarding women, Doniger shows that although texts like Manu’s dharma treat women as constrained and even dangerous—objects to be controlled or sources of moral hazard—the Ramayana, a contemporary of those texts, presents women as multidimensional characters whose flaws, passions, and defiant impulses add unexpected humor and complexity to the narrative. In other words, the women in the epic are not mere passive figures but are imbued with contradictions; their capacity for both virtue and transgression makes the story richer and more unpredictable.

Likewise, the monkeys play a crucial role by acting as unofficial doubles or “shadows” of the human characters. They are portrayed in a manner that is far more earthy and human—speaking Sanskrit, debating ethical dilemmas, and even displaying familial squabbles—thus providing a playful counterpoint to the lofty ideals of the human heroes. Their mimicry and the ironic gaps between their behavior and that of their human counterparts reveal the inherent ambiguities and ironies within the epic. In essence, these monkey doubles, with all their humorous and relatable imperfections, reveal that beneath the surface of heroic grandeur lies a more textured, dynamic, and even absurd reality.

Thus, by highlighting the roles of both women and monkeys, Doniger is not merely pointing out exotic or marginal elements; she is emphasizing that the true “fun” of the Ramayana—and by extension, of Hindu narrative tradition—lies in its capacity to disrupt ideal forms with human complexity, ambiguity, and even a sense of playful irreverence.

CHAPTER 10 – VIOLENCE IN THE MAHABHARATA 300 BCE to 300 CE

Turning to the Mahabharata, Doniger investigates the epic’s extensive treatment of violence. Far from a glorification of brutality, the text is shown to wrestle with the ethical ambiguities of conflict and warfare. The narrative explores how the interplay between violence and the need for order reflects deeper truths about human nature and the moral dilemmas faced by individuals and societies.

Doniger focuses on the Mahabharata not merely as a long war‐epic but as a sprawling, multifaceted narrative that continuously interrogates the nature of dharma (moral duty) through its account of violence. The story itself is not a single, neatly packaged tale but a dynamic “conversation” that has been retold, reassembled, and reinterpreted over generations, so that no one version can claim final authority. Doniger reminds us that the Mahabharata “is not contained in a text” but rather exists as a living, fluid tapestry of stories woven together by oral and written traditions.

At its heart, the epic recounts the dynastic struggle between the Pandavas and the Kauravas—a bitter conflict over the rightful claim to the kingdom that culminates in the catastrophic Kurukshetra war. Throughout this struggle, every major character is forced to confront deep moral dilemmas. For instance, Arjuna’s crisis on the battlefield exemplifies the conflict between personal loyalty and his duty as a warrior. Overwhelmed by the prospect of fighting his own kin and teachers, Arjuna is paralyzed by doubt about whether the necessary violence of war can ever be reconciled with the higher demands of dharma. His conversation with Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita then becomes a profound exploration of how one can act righteously even in the face of unspeakable moral cost—a dilemma that resonates throughout the epic.

Doniger shows that the moral dilemmas in the Mahabharata are not resolved by neat prescriptions. Instead, the text repeatedly demonstrates that dharma is “subtle” (sukshma), slippery, and context‐dependent. Characters like Yudhishthira, who is celebrated for his steadfast commitment to righteousness, nonetheless struggle with the inevitable fallout of every decision made in a time of war, where every available moral option seems to carry its own tragic consequences. The epic’s portrayal of such dilemmas—whether it’s the ethical implications of fratricidal conflict, the consequences of bending moral rules to suit personal needs, or the internal battles between duty and compassion—underscores that no single set of rules can neatly adjudicate the complex realities of human life.

Moreover, the Mahabharata’s structure itself reinforces these themes. Its open-ended, ever-revisable narrative style—with hundreds of manuscripts and oral versions—mirrors the unresolved nature of moral conflict. Rather than offering a final verdict on right and wrong, the epic invites its audience to continually question: How does one live well when every action carries profound and often painful consequences? In this way, the text becomes a meditation on the human condition, challenging readers to reflect on the ambiguity of ethical choices and the cost of adherence to duty in a flawed world.

In sum, Chapter 10 presents the Mahabharata as an epic of relentless moral inquiry. Its story—a brutal, complex civil war between kin—serves as a stage upon which the perennial human struggle with duty, loyalty, and justice is played out. Doniger’s account emphasizes that the epic’s enduring power lies in its unflinching portrayal of the messy, often painful process of trying to do what is right when every available choice seems to entail significant moral compromise.

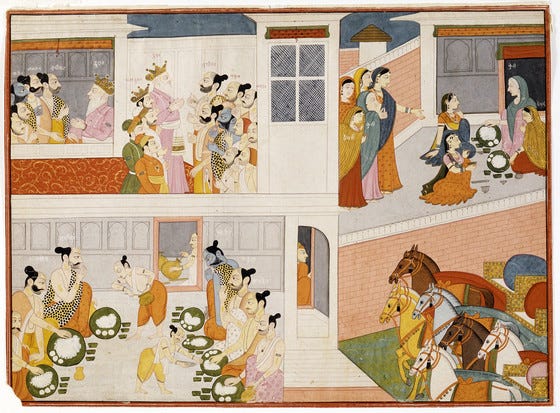

https://collections.lacma.org/node/198481

CHAPTER 11 – DHARMA IN THE MAHABHARATA 300 BCE to 300 CE

In a continuation of her analysis of the Mahabharata, this chapter focuses specifically on the concept of dharma. Doniger discusses how characters in the epic navigate conflicting duties and moral responsibilities. The fluidity and situational nature of dharma are central to understanding the epic’s enduring relevance and its portrayal of ethical uncertainty.

Doniger’s central insight is that the Mahabharata serves as a profound meditation on the inherent ambiguity and fluidity of dharma. Rather than offering a neat, absolute code of right and wrong, the epic exposes how every moral decision is fraught with contradictions and contextual nuances. This “subtlety of dharma” is encapsulated in moments like Yudhishthira’s famous query—“What is dharma?”—which is left unanswered because, as the text shows, moral principles are perpetually in conflict with one another in the messy reality of human life. In essence, the Mahabharata deconstructs the idea of a fixed moral order, suggesting that what is considered righteous depends on one’s specific duty (sva‑dharma), the circumstances at hand, and even the inevitable compromises that come with being human. This insight challenges readers to accept that moral dilemmas do not have tidy resolutions; instead, dharma remains elusive, dynamic, and deeply interwoven with the chaos of existence.

Krishna’s message to Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita—integral to Doniger’s insight on the ambiguity of dharma—is a call to engage with life’s complexities without clinging to simplistic notions of right and wrong. Faced with the prospect of fighting his own kin, Arjuna is paralyzed by the moral weight of his duty. Krishna, however, reframes the situation: he advises Arjuna to perform his duty (svadharma) without attachment to the results, emphasizing that the act itself, performed with selflessness, is what truly matters. This teaching—that one should act with dedication while surrendering the fruits of action to a higher cosmic order—embodies the subtle, fluid nature of dharma highlighted so well in these passages of the Mahabharata.

In this light, Krishna’s counsel is not just a prescription for war but a broader philosophical framework that has inspired countless spiritual seekers. The Gita’s message resonates because it acknowledges the inevitability of moral dilemmas: rather than offering tidy answers, it encourages individuals to navigate life’s inherent uncertainties by embracing a path of disciplined, detached action. For many, this approach provides both solace and a powerful guide for personal transformation, suggesting that ethical living isn’t about adhering to rigid dogmas but about finding balance in a world where every choice has its own set of contradictions.

This blend of practical action and deep spirituality has made the Gita one of the most influential texts in world spiritual literature. It teaches that while the external world may be rife with conflict and moral ambiguity, one can still achieve inner peace and clarity by focusing on duty and devotion. In doing so, Krishna’s words have offered a path to liberation that transcends the particularities of any one culture or historical moment—a path that continues to inspire and guide spiritual aspirants around the globe.

CHAPTER 12 – ESCAPE CLAUSES IN THE SHASTRAS 100 BCE to 400 CE

This chapter delves into the legal and ethical texts known as the Shastras. Doniger reveals how these texts incorporate “escape clauses” that allow for exceptions and reinterpretations. Such clauses expose the inherent tensions in trying to codify a living tradition and illustrate how law and morality were continuously negotiated within the social fabric of Hindu society.

Doniger shows that the shastras did not arise in a vacuum but were forged in a period of significant social and political flux between 100 BCE and 400 CE. Faced with the pressures of a rapidly changing society—marked by urbanization, shifting power structures, the growing influence of Buddhism and Jainism, and the challenges of governing a vast, heterogeneous population—the Brahminical elite sought to stabilize social order by codifying norms. The shastras emerged as detailed manuals of conduct that not only prescribed the ideal behavior for various classes but also ingeniously incorporated “escape clauses.” These clauses allowed for exceptions and reinterpretations when the realities of everyday life clashed with the rigid ideals of ritual and social hierarchy .

This adaptive quality meant that while the shastras eventually became the backbone of legal and ritual authority in later Hindu society, they were never entirely dogmatic. Their built-in flexibility allowed them to absorb and reflect changes over time—even as they sought to maintain a conservative vision of order. Later, as these texts became more entrenched, they played a dual role: they served both as a means to preserve traditional Brahminical power and as a reference point for reform and resistance among those who found the strict prescriptions unworkable in a modern or diversifying context.

CHAPTER 13 – BHAKTI IN SOUTH INDIA 100 BCE to 900 CE

This chapter traces the rise of devotional movements (bhakti) in South India. This period saw the emergence of a deeply personal and emotional form of worship that bypassed the traditional priestly hierarchy. Bhakti not only democratized religious experience by involving lower castes and women but also reshaped the very language and symbols of the divine.

Doniger traces the emergence of the Bhakti movements as a vibrant, transformative response to both spiritual longing and social rigidity in South India. These devotional movements arose during a period when the traditional Brahminical order—characterized by strict ritualism and rigid caste hierarchies—began to show its limits. Ordinary people, who had long been on the margins of the Sanskrit-dominated elite culture, found in Bhakti an alternative path that emphasized personal, heartfelt devotion to a chosen deity. This path was accessible because it was expressed in the vernacular and imbued with local poetic and musical traditions, making it immediately resonant with everyday life.

The story of Bhakti is also one of synthesis. As these movements spread, they interacted with existing religious traditions such as Jainism and Buddhism, which had earlier emphasized compassion and non-attachment, and later even with Sufi Islam, whose mystical dimensions underscored love and surrender. This intermingling produced a form of devotion that was both inclusive and challenging—it questioned established norms while simultaneously offering a powerful model for spiritual equality. In this way, Bhakti not only redefined the relationship between devotee and deity but also became a tool for social reform by cutting across caste and gender divisions.

Today, the legacy of the Bhakti movements endures. Their emphasis on personal love, emotional expression, and a direct, unmediated relationship with the divine continues to influence contemporary Hindu practice. Bhakti saints—whose songs, poems, and stories still echo in temples and public spaces—remain icons of a tradition that prizes experiential knowledge over ritualistic conformity. In modern times, this heritage of devotion offers spiritual seekers a path that is as much about inner transformation as it is about communal identity, reminding us that the journey to the divine can be as personal and varied as the individuals who undertake it.

CHAPTER 14 – GODDESSES AND GODS IN THE EARLY PURANAS 300 to 600 CE

In the early Puranas, myth and ritual converge to reconfigure earlier Vedic ideas into a more accessible pantheon. Doniger examines the transformation of deities—both male and female—and discusses how these texts made the divine more immediate to the common people. The interplay of myth, ritual, and iconography in this period lays the groundwork for the later, highly popularized forms of worship.

Doniger shows that both Hindu practice and myth undergo significant transformation as they are reconfigured to meet new historical demands. During the early Puranic period (roughly 300–600 CE), several historical pressures converge that force a reinterpretation of earlier, more fragmented traditions. First, as political authority became more centralized and regional kingdoms began asserting their power, there was a need for a coherent religious narrative that could support state legitimacy. In response, local deities and diverse ritual practices were reworked into a canon—the early Puranas—that not only standardized myth but also integrated previously marginal voices, particularly those of goddesses. This process helped create a more uniform religious identity across a vast, heterogeneous society.

At the same time, external influences—especially the competitive presence of Buddhism and Jainism—pushed Hindu traditions to articulate a distinct identity. The need to differentiate itself while still absorbing popular and local traditions led to a reimagining of divine figures and practices. Myths that once were polysemic and regionally varied became reinterpreted with new symbolic meanings that could serve both devotional purposes and the demands of an emerging bureaucratic state. In short, Hindu practice and myth changed by fusing diverse local and non‐Sanskrit elements into a more centralized, canonical form, which in turn allowed the tradition to remain dynamic yet cohesive in the face of shifting political and religious landscapes.

This evolution—where old gods and goddesses are reformulated to embody new ideals and where ritual practices are adapted to both popular devotion and elite patronage—reflects Doniger’s broader insight about the adaptive, ever-changing nature of Hinduism. The early Puranic reworking thus set the stage for later developments, providing a foundation that could absorb future challenges and incorporate new influences while still maintaining continuity with the past.

CHAPTER 15 – SECTS AND SEX IN THE TANTRIC PURANAS AND THE TANTRAS 600 to 900 CE

Doniger outlines Tantra as a transformative, often transgressive response to the rigid, ritualistic, and hierarchical framework of orthodox Hinduism. Its origins can be traced to a time when traditional Vedic rituals were increasingly seen as insufficient for addressing the deeper, more personal dimensions of spiritual experience. In reaction, a group of reformers and mystics began to experiment with methods that would not only incorporate but also valorize elements that had once been considered taboo—most notably sexual practices, ritual impurity, and unconventional symbolism. This innovative impulse led to the emergence of Tantra as a distinct, albeit diverse, tradition that reinterpreted the sacred, making the body and its desires potential vehicles for spiritual liberation .

Over time, Tantric practice evolved in both scope and complexity. Early Tantric texts were not standardized; they circulated in various local forms, often transmitted orally before being codified into manuscripts. As Tantra spread, it absorbed influences from local folk traditions, as well as from Buddhist and Jain practices, which contributed ideas about the transformation of ordinary experiences into sacred acts. This syncretism helped Tantra develop a richly textured set of practices that ranged from the highly esoteric and ritualistic to more accessible devotional forms. Many later texts and commentaries, produced by figures such as Abhinavagupta and other Tantric scholars, helped to systematize these ideas, linking sexual symbolism, mantra recitation, meditative practices, and even alchemical techniques into a coherent if multifaceted path toward liberation .

The driving ideas behind Tantra rest on a radical reimagining of the nature of divinity and the universe. Tantric practitioners posit that the divine is immanent in all aspects of existence—even in what orthodox views would deem impure or base. They argue that by harnessing the energies inherent in the body and the material world, including those expressed through sexual union and other taboo practices, one can catalyze an inner transformation that leads to liberation (moksha). In this framework, traditional boundaries between the sacred and the profane are deliberately blurred, and practices that invert social and religious hierarchies become powerful means of subversion and self-realization. Motivated by the desire to achieve a direct, experiential communion with the divine, Tantric movements often celebrate both the creative and the destructive forces of nature, emphasizing the dynamic interplay between opposites like purity and impurity, order and chaos.

CHAPTER 16 – FUSION AND RIVALRY UNDER THE DELHI SULTANATE 650 to 1500 CE

The Delhi Sultanate period brought significant cultural and religious contact between Hindu and Muslim communities. Doniger discusses how this era was marked by both fusion—evident in art, language, and ritual—and rivalry, as competing religious identities and political ambitions often clashed. The resulting hybridity is seen as a precursor to modern pluralism in India.

Chapter 16 presents the Delhi Sultanate as a transformative era when political conquest and cultural exchange dramatically reshaped the religious landscape of India. The Sultanate emerged in the 12th and 13th centuries as Muslim dynasties—beginning with figures like Qutb-ud-din Aibak and Iltutmish—established their rule over northern India. Initially, their arrival was marked by military campaigns and the imposition of Islamic administrative and legal frameworks. However, as Muslim rulers consolidated power over a region steeped in diverse indigenous traditions, a complex dialogue began between Islam and Hinduism, characterized by both rivalry and creative fusion .

On one level, the Delhi Sultanate imposed a new cultural and religious order through Persianate administration, art, and literature. Yet, rather than erasing Hindu traditions, the rulers gradually adapted to their new milieu. They absorbed many local practices and symbols—sometimes even incorporating Hindu motifs into Islamic art and architecture—while Hindu society, in turn, was influenced by Islamic ideas. For example, the mystical strains of Sufism, with its focus on personal devotion and an experiential understanding of the divine, resonated with and enriched emerging Bhakti practices. This mutual influence is evident in devotional literature, music, and even in the reinterpretation of ritual and ethics, where the rigid dichotomies of the past softened into more hybrid, inclusive expressions of faith.

This progressive interaction had profound and lasting impacts. The rivalry between the two traditions—manifesting in episodes of conflict and even temple desecration—was tempered by a creative exchange that reconfigured cultural boundaries. Over time, local Hindu elites and popular traditions absorbed elements of Islamic art, language, and spirituality, leading to a unique Indo-Islamic culture that persists today. Thus, rather than a one-way imposition, the period is best understood as one of dynamic interplay, where both traditions challenged and enriched one another. The result was a pluralistic and syncretic society, one in which religious identities were continually renegotiated in response to the practical realities of governance and the enduring human quest for meaning .

CHAPTER 17 – AVATAR AND ACCIDENTAL GRACE IN THE LATER PURANAS 800 to 1500 CE

Doniger investigates the development of the avatar concept in the later Puranas. She explores how divine incarnations, particularly those of Vishnu, became a central motif in offering hope and moral guidance. The narratives of accidental grace—where divine intervention appears almost serendipitously—reflect changing social conditions and the need for accessible models of salvation.

Chapter 17 describes how between 800 and 1500 CE, the idea of avatars—and especially the notion of “accidental grace”—revolutionized the way divine intervention and salvation were understood. During this period, as traditional ritual and Brahminical authority began to be questioned, the emergence of avatars (divine incarnations) provided a way to make the divine accessible on a personal level. Avatars, particularly those of Vishnu, were seen not as meticulously planned, deterministic events but as spontaneous, even “accidental” interventions that bestowed grace on humanity regardless of strict ritual adherence.

This idea of accidental grace is crucial because it reoriented the path to salvation from one based solely on rigorous, and often exclusionary, ritual practices toward one that emphasizes divine compassion and the unpredictable generosity of the gods. It meant that even those who might have strayed from prescribed paths could still receive the saving grace of the divine through an avatar’s unexpected appearance. For many believers of that era, this was deeply liberating—it democratized spiritual attainment and offered hope to the marginalized who were not fully integrated into the orthodox system.

For today’s spiritual seekers, accidental grace continues to hold significant appeal. It offers a reassuring message that salvation isn’t confined to the elite or the perfectly observant, but is available as a gift, sometimes arriving unexpectedly and transforming lives regardless of past failings. This idea encourages a more personal, loving, and inclusive approach to spirituality—one that emphasizes devotion over rigid legalism. In modern practice, many find that this liberating perspective helps bridge the gap between ancient tradition and contemporary life, reinforcing the belief that divine mercy can be both unpredictable and boundless.

https://www.hinduismtoday.com/magazine/november-1997/1997-11-the-path-of-grace/

CHAPTER 18 – PHILOSOPHICAL FEUDS IN SOUTH INDIA AND KASHMIR 800 to 1300 CE

Doniger turns to the intellectual ferment of South India and Kashmir, where fierce philosophical debates enriched the spiritual landscape. In Chapter 18 Doniger details how medieval India became an intellectual crucible for competing ideas. Over several centuries—from roughly 800 to 1300 CE—various philosophical schools emerged in different regions as scholars sought answers to fundamental questions about reality, knowledge, and liberation. These debates arose in response to a dynamic social and political environment marked by the collapse of older orders and the need for new frameworks to interpret life.

Scholars from orthodox traditions such as Mimamsa and Vedanta—focused on interpreting the Vedas, ritual practice, and the nature of ultimate reality—engaged in rigorous debate with rationalist schools like Nyaya and Vaisheshika, which emphasized logic and systematic inquiry into perception and inference. In parallel, heterodox traditions like Samkhya and early Buddhist and Jain philosophies offered dualistic and alternative perspectives on consciousness, suffering, and the path to moksha. Each of these schools emerged in diverse locales, from the scholarly hubs of North India to the vibrant cultural centers in Kashmir and South India, shaped by local power struggles and the need to negotiate shifting social hierarchies.

Renowned philosophers and court scholars participated in these debates, often sponsored by regional rulers who needed a coherent ideological framework to legitimize their authority. The “what” centered on core questions: What is the nature of the self? How do we know what is true? What is the role of ritual and ethical behavior? And ultimately, what constitutes liberation?

These debates influenced subsequent movements—such as Bhakti and Sufism—that built on the idea that truth is multifaceted, and that spiritual insight emerges from ongoing dialogue rather than from rigid dogma, that practice takes pride of place over theorizing. Today, these debates continue to inspire modern scholars and spiritual seekers alike. They serve as a reminder that ambiguity and pluralism are not weaknesses but strengths in the pursuit of wisdom, encouraging openness to multiple perspectives and a recognition that ethical and metaphysical questions are best approached as dynamic conversations rather than fixed answers.

CHAPTER 19 – DIALOGUE AND TOLERANCE UNDER THE MUGHALS 1500 to 1700 CE

During the Mughal era, Hinduism was transformed by sustained interactions with Islam. Doniger illustrates how this period witnessed a remarkable dialogue and, at times, a genuine tolerance between communities. Mughal rule—especially under emperors like Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan—created a uniquely vibrant milieu for intra‐religious dialogue that reshaped both Islam and Hinduism. During this period, imperial policies encouraged scholars, mystics, and artists from different traditions to engage in open discussion. Akbar’s establishment of institutions like the Ibadat Khana (House of Worship) provided a formal arena where theologians and philosophers from Islam, Hinduism, Jainism, and even Christianity could debate and share ideas. This dialogue was not merely academic; it penetrated everyday culture, influencing literature, music, art, and even court rituals.

The intense interaction between these two traditions was driven by both conflict and creative synthesis. While there were undoubtedly episodes of military and political strife, the everyday reality was one of profound mutual influence. In turn, Hindu ritual and iconography found new expression in the ornate, syncretic art of the Mughal court, as seen in architecture and miniature painting that melded Persian styles with indigenous motifs. This ongoing exchange led to a softening of rigid doctrinal boundaries. Islamic theology absorbed aspects of local Hindu thought—such as ideas about cosmic order and the multiplicity of divine forms—while Hindu practices incorporated Persianate aesthetics and Sufi metaphors. As a result, both communities began to see the other not simply as an opponent but as a source of enriching ideas, a transformation that paved the way for a more pluralistic cultural identity. Today, this legacy of dialogue and creative tension is visible in the enduring Indo-Islamic culture that continues to shape spiritual and artistic expressions across South Asia.

https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2015/09/sanskrit-mughal-empire-090915

CHAPTER 20 – HINDUISM UNDER THE MUGHALS 1500 to 1700 CE

Chapter 20 deepens the picture drawn in Chapter 19 by showing that under Mughal rule Hinduism was not simply pressured or suppressed but actively reshaped by a dynamic interplay with Islamic culture. Doniger explains that the Mughal state—particularly during periods of enlightened rule like Akbar’s—created a cosmopolitan space where Hindu and Muslim intellectuals, artists, and religious practitioners met and exchanged ideas. This dialogue was institutionalized in courtly settings: debates, translations, and even joint patronage of art and literature flourished, resulting in a distinctive Indo-Islamic cultural synthesis.

Under the Mughals, Hindu ritual practice and myth took on new hues. For instance, Hindu deities were sometimes reimagined through the aesthetic and philosophical lenses of Persian literature and Sufi mysticism. This led to the incorporation of motifs such as love, mysticism, and the interplay between beauty and devotion into devotional practices—a trend that enriched the Bhakti movements further. Meanwhile, Muslim art and literature absorbed indigenous Hindu themes and symbols, resulting in architecture and miniature painting that seamlessly blended Persian refinement with the bold, earthy elements of local traditions.

The Mughal rulers themselves played a key role in this transformative process. While some, like Akbar, promoted religious pluralism and even commissioned translations of Sanskrit texts into Persian, others such as Aurangzeb imposed stricter religious codes. Nevertheless, even during more intolerant periods, the underlying cultural exchange did not entirely cease; everyday practices and popular forms of worship continued to reflect a long history of mutual influence. Today, this legacy is evident in the syncretic expressions of art, music, and literature found across South Asia, and it remains a touchstone for contemporary debates on religious tolerance and cultural identity.

CHAPTER 21 – CASTE, CLASS, AND CONVERSION UNDER THE BRITISH RAJ 1600 to 1900 CE

This chapter addresses the profound social transformations under British colonial rule. Doniger discusses how the British reified and redefined caste and class divisions, often through legal and administrative mechanisms. Conversion—whether voluntary or coerced—became a critical theme, as Hindu identity was reinterpreted in the context of colonial power dynamics.

Doniger recounts how British colonization radically reconfigured Indian identities and religious practices by imposing a new framework of categorization and political control that was alien to the precolonial pluralism of India. The British arrived with their own understandings of “religion” as a fixed, institutional entity—a concept that did not naturally align with the fluid, multifaceted traditions of Hinduism. By creating censuses and legal definitions that lumped diverse practices under the single label “Hindu,” the colonial state not only redefined what it meant to be Indian but also reshaped indigenous practices.

British colonial policies played a crucial role in reshaping India’s religious landscape by promoting a homogenized vision of Hinduism that often erased regional and sectarian distinctions. One of the primary methods was through systematic categorization. Beginning with the census operations in the late 19th century, the British classified Indians under fixed religious labels, forcing an eclectic array of local practices and traditions into the single category of “Hindu.” This administrative decision effectively reified Hinduism as a unified religion, despite its inherent pluralism and diversity.

In addition, the colonial legal framework contributed significantly to this process. Customary laws that once varied considerably from region to region were gradually codified into a standardized body of “Hindu law.” Through legal judgments and the creation of the Hindu Code Bills, practices that had evolved independently in different parts of India were either ignored or reinterpreted in light of a Brahmin-centric textual tradition. British ethnographers and administrators, such as Sir William Jones, further reinforced this trend by emphasizing Sanskrit scriptures—the Vedas, Upanishads, and related texts—as the defining authorities of Hindu identity, even when popular practices diverged from these canonical sources.

Furthermore, the educational policies implemented by the colonial state promoted a uniform narrative. British-established schools and universities taught a version of Hinduism that was distilled from the scholarship of Orientalists. This version highlighted a static, “timeless” religious tradition rather than a living, evolving one, thereby marginalizing regional variations and alternative interpretations. The overall effect was to create a public and legal identity that aligned more closely with the British administrative needs—ensuring social order and facilitating governance—than with the complex realities of indigenous belief and practice.

Under British rule, Indian religious life became increasingly politicized. The colonial administrators and Christian missionaries, in their drive to systematize and often “modernize” Indian society, inadvertently set the stage for new forms of self-identification. Traditional practices and local deities were reinterpreted through a Western lens, while rigid caste and class distinctions were both challenged and reinforced in complex ways. As Indian elites and reformers began to react against the homogenizing impulses of colonial rule, they often rearticulated their religious traditions to emphasize aspects—such as devotional fervor or ethical order—to reclaim a sense of national and cultural pride.

At the same time, the encounter with British legal and administrative systems led to the codification of rituals and practices that had previously been much more fluid and regionally diverse. This not only transformed everyday religious behavior but also impacted the way history was written and understood, as the colonial narrative of a “timeless” Hindu tradition was upended by evidence of ongoing change and adaptation. The legacy of British colonization is still felt today, as the modern Indian religious landscape continues to wrestle with the dual inheritance of its indigenous pluralism and the imposed categories of the colonial era.

CHAPTER 22 – SUTTEE AND REFORM IN THE TWILIGHT OF THE RAJ 1800 to 1947 CE

Focusing on the practice of suttee (widow immolation) and other controversial rites, Doniger explores the reform movements that emerged in the late colonial period. Debates among reformers, nationalists, and traditionalists over practices like suttee are emblematic of the tensions between modernity and tradition.

The story of suttee is multifaceted. Suttee—the practice of widow immolation— illustrates how both colonial and indigenous forces drove profound change. Doniger explains that the British colonial administration, with its emphasis on rationality and humanitarian reform, brought suttee under intense scrutiny. British officials and missionaries, alarmed by what they perceived as a cruel, archaic practice, pushed for legal intervention. Yet, as the debate over suttee intensified in public forums and colonial courts, many Indians themselves began to question and reinterpret the ritual within their own cultural context.

Indigenous reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy emerged as vocal critics. They argued that suttee was not an immutable religious duty but a practice that had become distorted over time. By drawing on emerging ideas about human rights and modernity—ideas that the British had introduced—they mounted vigorous campaigns for its abolition. These reformers organized public debates, engaged with colonial legislative bodies, and used print media to galvanize opinion against the ritual. Their arguments were not merely imported critiques; they were deeply rooted in indigenous ethical debates that had questioned the status of women long before British intervention.

At the same time, local communities across different regions exhibited a spectrum of responses. In some villages and regional centers, suttee was reinterpreted rather than outright rejected. There were instances where the ritual was transformed into a symbolic act of mourning rather than literal self-immolation, reflecting a bottom-up effort to adapt traditional practices to contemporary sensibilities. Local actors negotiated with both established religious authorities and the pressures of colonial governance, demonstrating that the drive for reform was as much a product of internal debates as it was of external pressure.

Thus, the story Doniger tells in Chapter 22 is one of dynamic interaction. The British insistence on categorizing and reforming Indian rituals forced a confrontation with age-old practices, while Indian reformers and local communities actively reshaped the narrative. This dual process of top–down imposition and bottom–up adaptation not only led to the eventual banning of suttee in the early 19th century but also played a significant role in the redefinition of modern Indian identity. It paved the way for a new discourse on gender, duty, and tradition—one in which change was seen as both necessary and possible. Today, the legacy of these debates informs ongoing discussions about the balance between preserving cultural heritage and embracing social reform, reminding us that religious practices are continuously reinterpreted by the very people who live them.

CHAPTER 23 – HINDUS IN AMERICA 1900 –

The arrival of Hindus in America followed a pattern of migration influenced by shifting political and economic landscapes. The first major wave of Hindu migration began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Swami Vivekananda attended the 1893 Parliament of Religions in Chicago and introduced Vedanta philosophy to a Western audience. His influence laid the groundwork for a philosophical and non-ritualistic form of Hinduism to take root in the United States, particularly among American intellectuals drawn to Eastern spirituality.

Later, the post-1965 Immigration Act in the United States opened the doors for a second wave of Indian migrants, primarily professionals in medicine, engineering, and academia. These immigrants sought to preserve Hindu traditions by constructing temples, which quickly became cultural hubs as much as religious sites. Unlike traditional temples in India, which are regionally and linguistically specific, American Hindu temples often serve multiple communities and house deities from various Indian traditions under one roof.

One of the most striking examples of this phenomenon is the Swaminarayan Mandir in Lilburn, Georgia, built for $19 million. Modeled not after an Indian temple but after the Swaminarayan temple in London, this temple represents a second-degree reinvention of Hindu architecture—a structure already shaped by Indian migration to Britain before being transplanted to the United States.

Unlike in India, where temples are often centers of pilgrimage, temples in the United States function as multi-purpose institutions. They serve not just as places of worship but also as sites of social integration, cultural preservation, and interfaith dialogue. Many temples offer:

Language classes (teaching Sanskrit, Hindi, Tamil, and Telugu to American-born Hindus).

Festivals adapted to American settings (Diwali and Navaratri celebrations that incorporate local customs).

Educational outreach (yoga and philosophy classes aimed at both Hindus and non-Hindus).

Doniger emphasizes how the idea of “local sacredness” has shifted—instead of entirely replacing India-based pilgrimage, many American Hindus engage in “virtual Hinduism”, where pujas and rituals are outsourced to priests in India. Websites now offer live-streamed darshans of major temples like Varanasi’s Vishwanath Mandir, and prasad (holy food) can be delivered across the ocean.

A major theme in this chapter is the commodification and appropriation of Hindu traditions in America. Doniger identifies three main objections from Hindus regarding how Hinduism is interpreted in the West:

Misrepresentation of Hinduism – American versions of Tantra and Kali worship often focus on exoticized, sexualized, or violent aspects, disregarding their deep spiritual and theological roots.

Selective Acceptance of Hinduism – Some American scholars dismiss Bhakti Hinduism as “folk religion” while celebrating Vedanta and the Bhagavad Gita, leading to a distorted view of Hindu thought.

Commercial Exploitation – Hindu symbols and deities are often stripped of religious significance and used for marketing. For example, Ben & Jerry’s “Karamel Sutra” ice cream and “Kama Sutra Chocolates” represent a profitable misinterpretation of Hindu texts.

Perhaps the most controversial example of Hinduism’s misrepresentation was the 1999 episode of Xena: Warrior Princess, which featured Krishna and Kali as characters in a fictionalized adventure. This led to protests from Hindu organizations, forcing the network to edit and re-release the episode with a disclaimer.

The second-generation Hindu experience in America is markedly different from that of their immigrant parents. Doniger explores how American-born Hindus navigate dual identities—balancing traditional Hindu customs with the values of a highly individualistic, secular, and multicultural society.

Reinterpretation of Rituals – Younger Hindus tend to favor personalized spiritual practices over rigid temple rituals. Many engage in yoga and meditation but are less likely to follow caste-based traditions or elaborate pujas.

Decentralization of Hindu Authority – Unlike in India, where temples and priests act as religious gatekeepers, American Hindus often seek spiritual guidance from online sources, books, and self-study.

Rise of Hindu Activism – Hindu organizations in America have pushed back against misrepresentations in media and textbooks, arguing for a more balanced depiction of Hindu history.

Doniger also discusses “reverse colonization”, a term she uses to describe how Hindu ideas have influenced American culture. While British imperialism once exported Western ideas to India, Hinduism has now “colonized” American spirituality in more subtle ways.

Yoga as a Global Phenomenon – Originally a Vedic and ascetic practice, yoga has become a multi-billion dollar industry in the U.S., often stripped of its religious significanceThe-Hindus-An-Alternati….

Influence on New Age Movements – Concepts like karma, reincarnation, and chakras have been integrated into mainstream American spirituality, often without reference to their Hindu origins.

Hindu Gurus in America – Figures such as Swami Vivekananda, A.C. Bhaktivedanta (founder of ISKCON), Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and Osho (Bhagwan Rajneesh) have shaped Western perceptions of Hinduism, sometimes leading to controversial adaptations.

CHAPTER 24 – THE PAST IN THE PRESENT 1950 –

Doniger argues that modern India is a palimpsest where the ancient is continuously rewritten to serve contemporary purposes. She shows how historical memory is not a static repository but a living force that Indian society and its political actors actively mobilize. Here are some specific examples and details from her analysis:

Doniger explains that modern Indian narratives often idealize an ancient “golden age” drawn from the Vedic and epic traditions. This idealized past is frequently evoked in political speeches, textbooks, and cultural festivals. For example, leaders and reformers invoke the timeless authority of texts like the Vedas or the epics, even though these texts themselves have undergone centuries of reinterpretation. This selective memory reinforces a notion of an unchanging Hindu civilization, thereby marginalizing the historical realities of transformation and diversity. She details how institutions—ranging from museums to the state’s educational system—have been used to assemble disparate traditions into a single, cohesive narrative. In doing so, modern India is presented as a continuum with an ancient past, even though indigenous practices and beliefs have been in constant flux. This narrative, while fostering a sense of unity and pride, also serves political ends by providing legitimacy to contemporary power structures.

Here, Doniger explores how ancient Hindu traditions, myths, and practices continue to shape contemporary India. She discusses the interplay of history and modern identity, showing how elements of Hinduism remain alive in unexpected ways, from political movements to caste dynamics and gender roles. She particularly examines the transformation of ancient texts and practices as they adapt to the modern world. Here are a few examples:

Multiplicity of the Ramayanas

The Ramayana is not a singular text but a tradition of multiple tellings across different regions, languages, and ideological frameworks. Doniger highlights key variations:

Valmiki's Sanskrit Ramayana (classical version) vs. Tulsidas' Ramcharitmanas (bhakti-oriented retelling in Awadhi).

South Indian versions, such as the Tamil Kamba Ramayanam, which introduce different emphases on heroism and devotion.

Tribal and Dalit Ramayanas, which portray Rama in a less divine light and elevate Ravana or Sita as central figures.

Feminist retellings, which reinterpret Sita's agency, questioning her suffering and submissiveness.

Tamil separatists have even produced their own Ramayana, positioning Ravana as a heroic Dravidian king resisting Aryan domination.

The Causeway to Lanka

The legendary Ram Setu (Adam’s Bridge), the causeway Rama and his army built to cross into Lanka, continues to be a politically and religiously charged symbol in India. Some Hindutva groups claim it is an actual man-made structure, while scientific studies suggest it is a natural formation. The tension between mythology and archaeology exemplifies how the past is used in modern nationalist debates.

Bollywood's Ramayana and Mahabharata

Doniger suggests that film and television adaptations of Hindu epics, such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata, have significantly shaped modern Hindu consciousness. These include:

Ramayan (1987-88) – The iconic TV series by Ramanand Sagar.

Mahabharat (1988-90) – The TV adaptation by B.R. Chopra.

Adipurush (2023) – A recent Bollywood take on the Ramayana. These adaptations can be streamed on platforms such as YouTube, Amazon Prime, and Netflix.

New Variations of Sita, Kunti, and Ekalavya